Jenny didn’t have much in the way of bowel symptoms, just bloating after meals and some constipation. She came in to see me because of severe fatigue, brain fog, thinning hair, and a history of infertility, and she wanted advice on what supplements might be helpful for these problems. As soon as I heard her rattle off this list of seemingly unrelated symptoms, however, I suspected an underlying autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases tend to travel in packs, since whatever is stimulating the immune system likely affects multiple organs, and are most common in women. I have lots of patients with autoimmune combinations like Crohn’s and psoriasis, or celiac disease and hypothyroidism.

Jenny’s blood work came back showing slightly abnormal thyroid function consistent with an underactive thyroid, which could definitely explain some of her symptoms. So I sent her to my local go-to thyroid expert. He checked some additional labs that confirmed hypothyroidism and started her on a low dose of thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Jenny perked up a little on this regimen and her bowel movements became a bit more regular, but she still didn’t feel quite right. We gave it another three months and rechecked her thyroid hormone levels. Everything was now perfectly in range, and she was tolerating the medication without any side effects. There was only one problem: she still didn’t feel well. I believed Jenny when she said she was bone-tired. She looked fatigued just walking from the waiting room to the exam room, and she described feeling “out of it” at work.

A slightly low iron level was what ultimately tipped me off to what might be going on. Further testing revealed mild anemia, low vitamin D, and low magnesium. With so many different nutrients affected, malabsorption was now high on the list of culprits. I sent off a test for celiac disease I commonly use that checks for three different antibodies (anti-tissue transglutaminase, endomysial, and anti-gliadin), as well as two genetic subtypes associated with the disease (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8).

Jenny’s test was strongly positive, with an estimated increased risk for celiac disease of thirty-one times higher than the general population. Since the prevalence of celiac disease in the United States is a little under 1 percent, her results were highly suggestive.

But I still didn’t know for certain that Jenny had celiac disease. The blood test can predict risk, but without seeing the characteristic changes in her intestines, I couldn’t be sure.

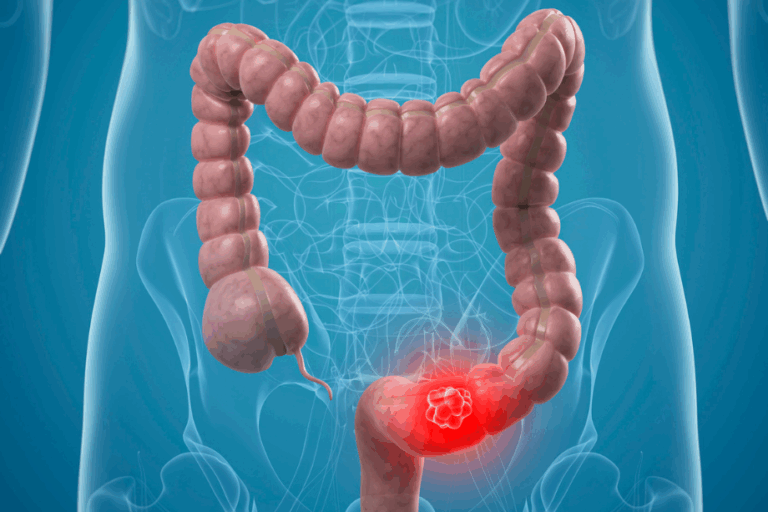

Celiac disease would certainly explain all of Jenny’s symptoms. Now I needed to see if she had it. Upper endoscopy allows me to take biopsies of the lining of the small intestine that can be examined under the microscope to confirm the two characteristic findings: flattening of the fingerlike projections of the small intestine called villi that are designed to pull nutrients from digested matter as it passes through the GI tract and send them to the rest of the body; and an increase in white blood cells called lymphocytes, signaling the body’s alerted immune response.

Jenny’s biopsies had both findings. And yet another piece of the puzzle fell into place with this diagnosis. Jenny had mentioned she’d had a stress fracture while skiing the previous winter, and a bone density study showed osteoporosis. At the time, this diagnosis was a surprise, since she was only thirty-two and not in the age group most at risk. Now it all made perfect sense: osteoporosis is strongly linked with celiac disease because of poor calcium absorption.

When I diagnose someone with celiac disease, I usually regard it as good news. Typically the patient, like Jenny, has been suffering for years with no answers as to why he or she feels so poorly and is in deteriorating health. When the diagnosis is finally made, it can feel like a light at the end of the tunnel, as well as validation that the symptoms are real— something that doctors along the way may have doubted. Best of all, celiac disease is treated by simply removing gluten from the diet. Occasionally someone has symptoms that don’t improve despite eliminating gluten from the diet, and prescription medications have to be used, but that’s rare.

So Jenny was relieved, but she was also perplexed. She felt poorly all the time, not just when she ate typical gluten containing foods like wheat, rye, or barley. I explained that over time, as a result of frequent exposure to gluten, the intestinal villi become flattened and are unable to absorb nutrients properly, especially iron, magnesium, calcium, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. When food isn’t properly absorbed, there can also be additional fermentation by bacteria, leading to bloating and diarrhea—although constipation like Jenny was experiencing can also occur.

Jenny had questions about medications, diet, pregnancy, and whether having celiac put her at risk for any cancers. I assured her that although there was a slightly higher incidence of lymphoma of the small bowel in untreated celiac disease, people in remission on a gluten-free diet (GFD) had no increased risk over the general population. There was more good news: the need for any medication to treat the disease was extremely low, and there was a good chance her infertility was a result of her celiac disease, which meant it would likely respond to the diet. Her thyroid condition, which had been diagnosed as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, was likely also related, since autoimmune thyroid diseases like Hashimoto’s are more common in people with celiac disease. The damage to the small intestine lining in celiac disease increases permeability in the gut, allowing toxic particles to gain access to the bloodstream and trigger an immune response in different organs, including the thyroid gland. People with the combination of celiac and thyroid disease are often able to treat both conditions through elimination of gluten. Jenny wasn’t suffering from multiple different ailments; her problems were all related to the effect of gluten on various parts of her body. And chances were that all of them would be improved by getting rid of gluten.

We spent most of Jenny’s follow-up visit talking about her diet. Avoiding wheat, rye, and barley may sound pretty straightforward, but if you eat out frequently or buy prepared or packaged foods, it can be a big adjustment. Wheat is used as filler in lots of foods, and barley is often used as a sweetener, so you have to read labels carefully. My advice to Jenny was to stick to foods that didn’t have an ingredient list: fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, eggs, potatoes, beans, yams, meat, poultry, fish, and shellfish. This was a great opportunity for her to eat “close to the ground” by avoiding packaged processed foods, and to discover some new grains.

In addition to brown rice, which she already ate a lot of, there was quinoa, cornmeal, amaranth, millet, and buckwheat. Oats can be problematic as they’re often processed in facilities that also process wheat, barley, and rye, so there may be contamination with gluten, but in my experience most people with celiac disease have no problem tolerating oats that are certified gluten-free.

The one trap I asked her to be sure to avoid was consuming a lot of gluten-free but nutritionally empty foods like cookies, cakes, crackers, breakfast cereal, pancakes, bread, and pizza. Celiac disease developed because of the introduction of refined grains into our diet that our small intestines can’t digest. Gluten-free junk is still junk, and swapping one refined grain for another can only lead to trouble down the road. People with celiac disease who eat a lot of gluten-free versions of foods that would normally have gluten in them, like pasta, cookies, bread, and pastries, generally have a much less robust response to their GFD. I encouraged Jenny to think about the fact that this disease was actually forcing her to behave in a way that conferred a real survival advantage: she would have to think about what she was eating, plan her meals carefully, avoid processed packaged foods, and cook more.

Jenny’s story had a very happy ending. Excited about the diet and the prospect of feeling better, she plunged right in. But a month after starting the diet, she came to see me quite discouraged. She hadn’t noticed any difference at all in her symptoms and was worried that the diagnosis was incorrect. She had been so hopeful that a GFD was the answer. I reassured her that it could take several months for the changes in her small intestine to normalize and her symptoms to improve. Eight months later when I saw her again, she was off her thyroid medication, much less fatigued, with regular bowel movements, a full head of hair, and negative celiac antibodies on her blood test. Her bloating was gone but she still had a bulging midsection—she was five months pregnant!